Wave

In physics, a wave is a disturbance (an oscillation) that travels through space and time, accompanied by the transfer of energy.

Waves travel and the wave motion transfers energy from one point to another, often with no permanent displacement of the particles of the medium—that is, with little or no associated mass transport. They consist, instead, of oscillations or vibrations around almost fixed locations. For example, a cork on rippling water will bob up and down, staying in about the same place while the wave itself moves onwards.

One type of wave is a mechanical wave, which propagates through a medium in which the substance of this medium is deformed. The deformation reverses itself owing to restoring forces resulting from its deformation. For example, sound waves propagate via air molecules bumping into their neighbors. This transfers some energy to these neighbors, which will cause a cascade of collisions between neighbouring molecules. When air molecules collide with their neighbors, they also bounce away from them (restoring force). This keeps the molecules from continuing to travel in the direction of the wave.

Another type of wave can travel through a vacuum, e.g. electromagnetic radiation (including visible light, ultraviolet radiation, infrared radiation, gamma rays, X-rays, and radio waves). This type of wave consists of periodic oscillations in electrical and magnetic fields.

A main distinction can be made between transverse and longitudinal waves. Transverse waves occur when a disturbance creates oscillations perpendicular (at right angles) to the propagation (the direction of energy transfer). Longitudinal waves occur when the oscillations are parallel to the direction of propagation.

Waves are described by a wave equation which sets out how the disturbance proceeds over time. The mathematical form of this equation varies depending on the type of wave.

General features

A single, all-encompassing definition for the term wave is not straightforward. A vibration can be defined as a back-and-forth motion around a reference value. However, a vibration is not necessarily a wave. An attempt to define the necessary and sufficient characteristics that qualify a phenomenon to be called a wave results in a fuzzy border line.

The term wave is often intuitively understood as referring to a transport of spatial disturbances that are generally not accompanied by a motion of the medium occupying this space as a whole. In a wave, the energy of a vibration is moving away from the source in the form of a disturbance within the surrounding medium (Hall 1980, p. 8). However, this notion is problematic for a standing wave (for example, a wave on a string), where energy is moving in both directions equally, or for electromagnetic / light waves in a vacuum, where the concept of medium does not apply and the inherent interaction of its component is the main reason of it's motion and broadcasting. There are water waves on the ocean surface; light waves emitted by the Sun; microwaves used in microwave ovens; radio waves broadcast by radio stations; and sound waves generated by radio receivers, telephone handsets and living creatures (as voices).

It may appear that the description of waves is closely related to their physical origin for each specific instance of a wave process. For example, acoustics is distinguished from optics in that sound waves are related to a mechanical rather than an electromagnetic wave transfer caused by vibration. Concepts such as mass, momentum, inertia, or elasticity, become therefore crucial in describing acoustic (as distinct from optic) wave processes. This difference in origin introduces certain wave characteristics particular to the properties of the medium involved. For example, in the case of air: vortices, radiation pressure, shock waves etc.; in the case of solids: Rayleigh waves, dispersion etc.; and so on.

Other properties, however, although they are usually described in an origin-specific manner, may be generalized to all waves. For such reasons, wave theory represents a particular branch of physics that is concerned with the properties of wave processes independently from their physical origin.[1] For example, based on the mechanical origin of acoustic waves, a moving disturbance in space–time can exist if and only if the medium involved is neither infinitely stiff nor infinitely pliable. If all the parts making up a medium were rigidly bound, then they would all vibrate as one, with no delay in the transmission of the vibration and therefore no wave motion. This is impossible because it would violate general relativity. On the other hand, if all the parts were independent, then there would not be any transmission of the vibration and again, no wave motion. Although the above statements are meaningless in the case of waves that do not require a medium, they reveal a characteristic that is relevant to all waves regardless of origin: within a wave, the phase of a vibration (that is, its position within the vibration cycle) is different for adjacent points in space because the vibration reaches these points at different times.

Similarly, wave processes revealed from the study of waves other than sound waves can be significant to the understanding of sound phenomena. A relevant example is Thomas Young's principle of interference (Young, 1802, in Hunt 1992, p. 132). This principle was first introduced in Young's study of light and, within some specific contexts (for example, scattering of sound by sound), is still a researched area in the study of sound.

Mathematical description of one-dimensional waves

Wave equation

Consider a traveling transverse wave (which may be a pulse) on a string (the medium). Consider the string to have a single spatial dimension. Consider this wave as traveling

- in the

direction in space. E.g., let the positive

direction in space. E.g., let the positive  direction be to the right, and the negative

direction be to the right, and the negative  direction be to the left.

direction be to the left. - with constant amplitude

- with constant velocity

, where

, where  is

is

- independent of wavelength (no dispersion)

- independent of amplitude (linear media, not nonlinear).[2]

- with constant waveform, or shape

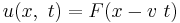

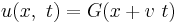

This wave can then be described by the two-dimensional functions

(waveform

(waveform  traveling to the right)

traveling to the right) (waveform

(waveform  traveling to the left)

traveling to the left)

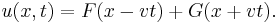

or, more generally, by d'Alembert's formula:[3]

representing two component waveforms  and

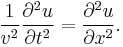

and  traveling through the medium in opposite directions. This wave can also be represented by the partial differential equation

traveling through the medium in opposite directions. This wave can also be represented by the partial differential equation

General solutions are based upon Duhamel's principle.[4]

Wave forms

The form or shape of F in d'Alembert's formula involves the argument x − vt. Constant values of this argument correspond to constant values of F, and these constant values occur if x increases at the same rate that vt increases. That is, the wave shaped like the function F will move in the positive x-direction at velocity v (and G will propagate at the same speed in the negative x-direction).[5]

In the case of a periodic function F with period λ, that is, F(x + λ − vt) = F(x − vt), the periodicity of F in space means that a snapshot of the wave at a given time t finds the wave varying periodically in space with period λ (the wavelength of the wave). In a similar fashion, this periodicity of F implies a periodicity in time as well: F(x − v(t + T)) = F(x − vt) provided vT = λ, so an observation of the wave at a fixed location x finds the wave undulating periodically in time with period T = λ/v.[6]

Amplitude and modulation

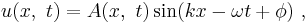

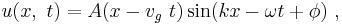

The amplitude of a wave may be constant (in which case the wave is a c.w. or continuous wave), or may be modulated so as to vary with time and/or position. The outline of the variation in amplitude is called the envelope of the wave. Mathematically, the modulated wave can be written in the form:[7][8][9]

where  is the amplitude envelope of the wave,

is the amplitude envelope of the wave,  is the wavenumber and

is the wavenumber and  is the phase. If the group velocity

is the phase. If the group velocity  (see below) is wavelength-independent, this equation can be simplified as:[10]

(see below) is wavelength-independent, this equation can be simplified as:[10]

showing that the envelope moves with the group velocity and retains its shape. Otherwise, in cases where the group velocity varies with wavelength, the pulse shape changes in a manner often described using an envelope equation.[10][11]

Phase velocity and group velocity

There are two velocities that are associated with waves, the phase velocity and the group velocity. To understand them, one must consider several types of waveform. For simplification, examination is restricted to one dimension.

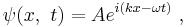

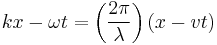

The most basic wave (a form of plane wave) may be expressed in the form:

which can be related to the usual sine and cosine forms using Euler's formula. Rewriting the argument,  , makes clear that this expression describes a vibration of wavelength

, makes clear that this expression describes a vibration of wavelength  traveling in the x-direction with a constant phase velocity

traveling in the x-direction with a constant phase velocity  .[12]

.[12]

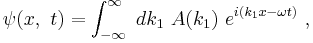

The other type of wave to be considered is one with localized structure described by an envelope, which may be expressed mathematically as, for example:

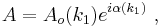

where now A(k1) (the integral is the inverse fourier transform of A(k1)) is a function exhibiting a sharp peak in a region of wave vectors Δk surrounding the point k1 = k. In exponential form:

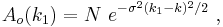

with Ao the magnitude of A. For example, a common choice for Ao is a Gaussian wave packet:[13]

where σ determines the spread of k1-values about k, and N is the amplitude of the wave.

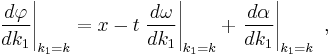

The exponential function inside the integral for ψ oscillates rapidly with its argument, say φ(k1), and where it varies rapidly, the exponentials cancel each other out, interfere destructively, contributing little to ψ.[12] However, an exception occurs at the location where the argument φ of the exponential varies slowly. (This observation is the basis for the method of stationary phase for evaluation of such integrals.[14]) The condition for φ to vary slowly is that its rate of change with k1 be small; this rate of variation is:[12]

where the evaluation is made at k1 = k because A(k1) is centered there. This result shows that the position x where the phase changes slowly, the position where ψ is appreciable, moves with time at a speed called the group velocity:

The group velocity therefore depends upon the dispersion relation connecting ω and k. For example, in quantum mechanics the energy of a particle represented as a wave packet is E = ħω = (ħk)2/(2m). Consequently, for that wave situation, the group velocity is

showing that the velocity of a localized particle in quantum mechanics is its group velocity.[12] Because the group velocity varies with k, the shape of the wave packet broadens with time, and the particle becomes less localized.[15] In other words, the velocity of the constituent waves of the wave packet travel at a rate that varies with their wavelength, so some move faster than others, and they cannot maintain the same interference pattern as the wave propagates.

Sinusoidal waves

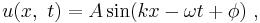

Mathematically, the most basic wave is the (spatially) one-dimensional sine wave (or harmonic wave or sinusoid) with an amplitude  described by the equation:

described by the equation:

where

is the maximum amplitude of the wave, maximum distance from the highest point of the disturbance in the medium (the crest) to the equilibrium point during one wave cycle. In the illustration to the right, this is the maximum vertical distance between the baseline and the wave.

is the maximum amplitude of the wave, maximum distance from the highest point of the disturbance in the medium (the crest) to the equilibrium point during one wave cycle. In the illustration to the right, this is the maximum vertical distance between the baseline and the wave. is the space coordinate

is the space coordinate is the time coordinate

is the time coordinate is the wavenumber

is the wavenumber is the angular frequency

is the angular frequency is the phase.

is the phase.

The units of the amplitude depend on the type of wave. Transverse mechanical waves (e.g., a wave on a string) have an amplitude expressed as a distance (e.g., meters), longitudinal mechanical waves (e.g., sound waves) use units of pressure (e.g., pascals), and electromagnetic waves (a form of transverse vacuum wave) express the amplitude in terms of its electric field (e.g., volts/meter).

The wavelength  is the distance between two sequential crests or troughs (or other equivalent points), generally is measured in meters. A wavenumber

is the distance between two sequential crests or troughs (or other equivalent points), generally is measured in meters. A wavenumber  , the spatial frequency of the wave in radians per unit distance (typically per meter), can be associated with the wavelength by the relation

, the spatial frequency of the wave in radians per unit distance (typically per meter), can be associated with the wavelength by the relation

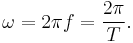

The period  is the time for one complete cycle of an oscillation of a wave. The frequency

is the time for one complete cycle of an oscillation of a wave. The frequency  is the number of periods per unit time (per second) and is typically measured in hertz. These are related by:

is the number of periods per unit time (per second) and is typically measured in hertz. These are related by:

In other words, the frequency and period of a wave are reciprocals.

The angular frequency  represents the frequency in radians per second. It is related to the frequency or period by

represents the frequency in radians per second. It is related to the frequency or period by

The wavelength  of a sinusoidal waveform traveling at constant speed

of a sinusoidal waveform traveling at constant speed  is given by:[16]

is given by:[16]

where  is called the phase speed (magnitude of the phase velocity) of the wave and

is called the phase speed (magnitude of the phase velocity) of the wave and  is the wave's frequency.

is the wave's frequency.

Wavelength can be a useful concept even if the wave is not periodic in space. For example, in an ocean wave approaching shore, the incoming wave undulates with a varying local wavelength that depends in part on the depth of the sea floor compared to the wave height. The analysis of the wave can be based upon comparison of the local wavelength with the local water depth.[17]

Although arbitrary wave shapes will propagate unchanged in lossless linear time-invariant systems, in the presence of dispersion the sine wave is the unique shape that will propagate unchanged but for phase and amplitude, making it easy to analyze.[18] Due to the Kramers–Kronig relations, a linear medium with dispersion also exhibits loss, so the sine wave propagating in a dispersive medium is attenuated in certain frequency ranges that depend upon the medium.[19] The sine function is periodic, so the sine wave or sinusoid has a wavelength in space and a period in time.[20][21]

The sinusoid is defined for all times and distances, whereas in physical situations we usually deal with waves that exist for a limited span in space and duration in time. Fortunately, an arbitrary wave shape can be decomposed into an infinite set of sinusoidal waves by the use of Fourier analysis. As a result, the simple case of a single sinusoidal wave can be applied to more general cases.[22][23] In particular, many media are linear, or nearly so, so the calculation of arbitrary wave behavior can be found by adding up responses to individual sinusoidal waves using the superposition principle to find the solution for a general waveform.[24] When a medium is nonlinear, the response to complex waves cannot be determined from a sine-wave decomposition.

Plane waves

Standing waves

A standing wave, also known as a stationary wave, is a wave that remains in a constant position. This phenomenon can occur because the medium is moving in the opposite direction to the wave, or it can arise in a stationary medium as a result of interference between two waves traveling in opposite directions.

The sum of two counter-propagating waves (of equal amplitude and frequency) creates a standing wave. Standing waves commonly arise when a boundary blocks further propagation of the wave, thus causing wave reflection, and therefore introducing a counter-propagating wave. For example when a violin string is displaced, transverse waves propagate out to where the string is held in place at the bridge and the nut, where the waves are reflected back. At the bridge and nut, the two opposed waves are in antiphase and cancel each other, producing a node. Halfway between two nodes there is an antinode, where the two counter-propagating waves enhance each other maximally. There is no net propagation of energy over time.

Physical properties

Waves exhibit common behaviors under a number of standard situations, e.g.,

Transmission and media

Waves normally move in a straight line (i.e. rectilinearly) through a transmission medium. Such media can be classified into one or more of the following categories:

- A bounded medium if it is finite in extent, otherwise an unbounded medium

- A linear medium if the amplitudes of different waves at any particular point in the medium can be added

- A uniform medium or homogeneous medium if its physical properties are unchanged at different locations in space

- An anisotropic medium if one or more of its physical properties differ in one or more directions

- An isotropic medium if its physical properties are the same in all directions

Absorption

Reflection

When a wave strikes a reflective surface, it changes direction, such that the angle made by the incident wave and line normal to the surface equals the angle made by the reflected wave and the same normal line.

Interference

Waves that encounter each other combine through superposition to create a new wave called an interference pattern. Important interference patterns occur for waves that are in phase.

Refraction

Refraction is the phenomenon of a wave changing its speed. Mathematically, this means that the size of the phase velocity changes. Typically, refraction occurs when a wave passes from one medium into another. The amount by which a wave is refracted by a material is given by the refractive index of the material. The directions of incidence and refraction are related to the refractive indices of the two materials by Snell's law.

Diffraction

A wave exhibits diffraction when it encounters an obstacle that bends the wave or when it spreads after emerging from an opening. Diffraction effects are more pronounced when the size of the obstacle or opening is comparable to the wavelength of the wave.

Polarization

A wave is polarized if it oscillates in one direction or plane. A wave can be polarized by the use of a polarizing filter. The polarization of a transverse wave describes the direction of oscillation in the plane perpendicular to the direction of travel.

Longitudinal waves such as sound waves do not exhibit polarization. For these waves the direction of oscillation is along the direction of travel.

Dispersion

A wave undergoes dispersion when either the phase velocity or the group velocity depends on the wave frequency. Dispersion is most easily seen by letting white light pass through a prism, the result of which is to produce the spectrum of colours of the rainbow. Isaac Newton performed experiments with light and prisms, presenting his findings in the Opticks (1704) that white light consists of several colours and that these colours cannot be decomposed any further.[25]

Mechanical waves

Waves on strings

The speed of a wave traveling along a vibrating string ( v ) is directly proportional to the square root of the tension of the string ( T ) over the linear mass density ( μ ):

where the linear density μ is the mass per unit length of the string.

Acoustic waves

Acoustic or sound waves travel at speed given by

or the square root of the adiabatic bulk modulus divided by the ambient fluid density (see speed of sound).

Water waves

- Ripples on the surface of a pond are actually a combination of transverse and longitudinal waves; therefore, the points on the surface follow orbital paths.

- Sound—a mechanical wave that propagates through gases, liquids, solids and plasmas;

- Inertial waves, which occur in rotating fluids and are restored by the Coriolis effect;

- Ocean surface waves, which are perturbations that propagate through water.

Seismic waves

Shock waves

Other

- Waves of traffic, that is, propagation of different densities of motor vehicles, and so forth, which can be modeled as kinematic waves[26]

- Metachronal wave refers to the appearance of a traveling wave produced by coordinated sequential actions.

Electromagnetic waves

(radio, micro, infrared, visible, uv)

An electromagnetic wave consists of two waves that are oscillations of the electric and magnetic fields. An electromagnetic wave travels in a direction that is at right angles to the oscillation direction of both fields. In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell showed that, in vacuum, the electric and magnetic fields satisfy the wave equation both with speed equal to that of the speed of light. From this emerged the idea that light is an electromagnetic wave. Electromagnetic waves can have different frequencies (and thus wavelengths), giving rise to various types of radiation such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet and X-rays.

Quantum mechanical waves

The Schrödinger equation describes the wave-like behavior of particles in quantum mechanics. Solutions of this equation are wave functions which can be used to describe the probability density of a particle.

de Broglie waves

Louis de Broglie postulated that all particles with momentum have a wavelength

where h is Planck's constant, and p is the magnitude of the momentum of the particle. This hypothesis was at the basis of quantum mechanics. Nowadays, this wavelength is called the de Broglie wavelength. For example, the electrons in a CRT display have a de Broglie wavelength of about 10−13 m.

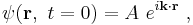

A wave representing such a particle traveling in the k-direction is expressed by the wave function:

where the wavelength is determined by the wave vector k as:

and the momentum by:

However, a wave like this with definite wavelength is not localized in space, and so cannot represent a particle localized in space. To localize a particle, de Broglie proposed a superposition of different wavelengths ranging around a central value in a wave packet,[28] a waveform often used in quantum mechanics to describe the wave function of a particle. In a wave packet, the wavelength of the particle is not precise, and the local wavelength deviates on either side of the main wavelength value.

In representing the wave function of a localized particle, the wave packet is often taken to have a Gaussian shape and is called a Gaussian wave packet.[29] Gaussian wave packets also are used to analyze water waves.[30]

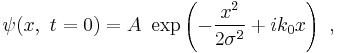

For example, a Gaussian wavefunction ψ might take the form:[31]

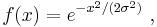

at some initial time t = 0, where the central wavelength is related to the central wave vector k0 as λ0 = 2π / k0. It is well known from the theory of Fourier analysis,[32] or from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle (in the case of quantum mechanics) that a narrow range of wavelengths is necessary to produce a localized wave packet, and the more localized the envelope, the larger the spread in required wavelengths. The Fourier transform of a Gaussian is itself a Gaussian.[33] Given the Gaussian:

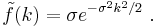

the Fourier transform is:

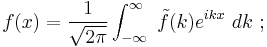

The Gaussian in space therefore is made up of waves:

that is, a number of waves of wavelengths λ such that kλ = 2 π.

The parameter σ decides the spatial spread of the Gaussian along the x-axis, while the Fourier transform shows a spread in wave vector k determined by 1/σ. That is, the smaller the extent in space, the larger the extent in k, and hence in λ = 2π/k.

Gravitational waves

Researchers believe that gravitational waves also travel through space, although gravitational waves have never been directly detected. Not to be confused with gravity waves, gravitational waves are disturbances in the curvature of spacetime, predicted by Einstein's theory of general relativity.

WKB method

In a nonuniform medium, in which the wavenumber k can depend on the location as well as the frequency, the phase term kx is typically replaced by the integral of k(x)dx, according to the WKB method. Such nonuniform traveling waves are common in many physical problems, including the mechanics of the cochlea and waves on hanging ropes.

References

- ^ Lev A. Ostrovsky & Alexander I. Potapov (2002). Modulated waves: theory and application. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801873258. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0801873258.

- ^ Michael A. Slawinski (2003). "Wave equations". Seismic waves and rays in elastic media. Elsevier. pp. 131 ff. ISBN 0080439306. http://books.google.com/?id=s7bp6ezoRhcC&pg=PA134.

- ^ Karl F Graaf (1991). Wave motion in elastic solids (Reprint of Oxford 1975 ed.). Dover. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780486667454. http://books.google.com/?id=5cZFRwLuhdQC&printsec=frontcover.

- ^ Jalal M. Ihsan Shatah, Michael Struwe (2000). "The linear wave equation". Geometric wave equations. American Mathematical Society Bookstore. pp. 37 ff. ISBN 0821827499. http://books.google.com/?id=zsasG2axbSoC&pg=PA37.

- ^ Louis Lyons (1998). All you wanted to know about mathematics but were afraid to ask. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128 ff. ISBN 052143601X. http://books.google.com/?id=WdPGzHG3DN0C&pg=PA128.

- ^ Alexander McPherson (2009). "Waves and their properties". Introduction to Macromolecular Crystallography (2 ed.). Wiley. p. 77. ISBN 0470185902. http://books.google.com/?id=o7sXm2GSr9IC&pg=PA77.

- ^ Christian Jirauschek (2005). FEW-cycle Laser Dynamics and Carrier-envelope Phase Detection. Cuvillier Verlag. p. 9. ISBN 3865374190. http://books.google.com/?id=6kOoT_AX2CwC&pg=PA9.

- ^ Fritz Kurt Kneubühl (1997). Oscillations and waves. Springer. p. 365. ISBN 354062001X. http://books.google.com/?id=geYKPFoLgoMC&pg=PA365.

- ^ Mark Lundstrom (2000). Fundamentals of carrier transport. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0521631343. http://books.google.com/?id=FTdDMtpkSkIC&pg=PA33.

- ^ a b Chin-Lin Chen (2006). "§13.7.3 Pulse envelope in nondispersive media". Foundations for guided-wave optics. Wiley. p. 363. ISBN 0471756873. http://books.google.com/?id=LxzWPskhns0C&pg=PA363.

- ^ Stefano Longhi, Davide Janner (2008). "Localization and Wannier wave packets in photonic crystals". In Hugo E. Hernández-Figueroa, Michel Zamboni-Rached, Erasmo Recami. Localized Waves. Wiley-Interscience. p. 329. ISBN 0470108851. http://books.google.com/?id=xxbXgL967PwC&pg=PA329.

- ^ a b c d Albert Messiah (1999). Quantum Mechanics (Reprint of two-volume Wiley 1958 ed.). Courier Dover. pp. 50–52. ISBN 9780486409245. http://books.google.com/?id=mwssSDXzkNcC&pg=PA52&dq=intitle:quantum+inauthor:messiah+%22group+velocity%22+%22center+of+the+wave+packet%22.

- ^ See, for example, Eq. 2(a) in Walter Greiner, D. Allan Bromley (2007). Quantum Mechanics: An introduction (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 60–61. ISBN 3540674586. http://books.google.com/?id=7qCMUfwoQcAC&pg=PA61.

- ^ John W. Negele, Henri Orland (1998). Quantum many-particle systems (Reprint in Advanced Book Classics ed.). Westview Press. p. 121. ISBN 0738200522. http://books.google.com/?id=mx5CfeeEkm0C&pg=PA121.

- ^ Donald D. Fitts (1999). Principles of quantum mechanics: as applied to chemistry and chemical physics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15 ff. ISBN 0521658411. http://books.google.com/?id=8t4DiXKIvRgC&pg=PA15.

- ^ David C. Cassidy, Gerald James Holton, Floyd James Rutherford (2002). Understanding physics. Birkhäuser. pp. 339 ff. ISBN 0387987568. http://books.google.com/?id=rpQo7f9F1xUC&pg=PA340.

- ^ Paul R Pinet (2009). op. cit.. p. 242. ISBN 0763759937. http://books.google.com/?id=6TCm8Xy-sLUC&pg=PA242.

- ^ Mischa Schwartz, William R. Bennett, and Seymour Stein (1995). Communication Systems and Techniques. John Wiley and Sons. p. 208. ISBN 9780780347151. http://books.google.com/?id=oRSHWmaiZwUC&pg=PA208&dq=sine+wave+medium++linear+time-invariant.

- ^ See Eq. 5.10 and discussion in A. G. G. M. Tielens (2005). The physics and chemistry of the interstellar medium. Cambridge University Press. pp. 119 ff. ISBN 0521826349. http://books.google.com/?id=wMnvg681JXMC&pg=PA119.; Eq. 6.36 and associated discussion in Otfried Madelung (1996). Introduction to solid-state theory (3rd ed.). Springer. pp. 261 ff. ISBN 354060443X. http://books.google.com/?id=yK_J-3_p8_oC&pg=PA261.; and Eq. 3.5 in F Mainardi (1996). "Transient waves in linear viscoelastic media". In Ardéshir Guran, A. Bostrom, Herbert Überall, O. Leroy. Acoustic Interactions with Submerged Elastic Structures: Nondestructive testing, acoustic wave propagation and scattering. World Scientific. p. 134. ISBN 9810242719. http://books.google.com/?id=UfSk45nCVKMC&pg=PA134.

- ^ Aleksandr Tikhonovich Filippov (2000). The versatile soliton. Springer. p. 106. ISBN 0817636358. http://books.google.com/?id=TC4MCYBSJJcC&pg=PA106.

- ^ Seth Stein, Michael E. Wysession (2003). An introduction to seismology, earthquakes, and earth structure. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 31. ISBN 0865420785. http://books.google.com/?id=Kf8fyvRd280C&pg=PA31.

- ^ Seth Stein, Michael E. Wysession (2003). op. cit.. p. 32. ISBN 0865420785. http://books.google.com/?id=Kf8fyvRd280C&pg=PA32.

- ^ Kimball A. Milton, Julian Seymour Schwinger (2006). Electromagnetic Radiation: Variational Methods, Waveguides and Accelerators. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 3540293043. http://books.google.com/?id=x_h2rai2pYwC&pg=PA16. "Thus, an arbitrary function f(r, t) can be synthesized by a proper superposition of the functions exp[i (k·r−ωt)]..."

- ^ Raymond A. Serway and John W. Jewett (2005). "§14.1 The Principle of Superposition". Principles of physics (4th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 433. ISBN 053449143X. http://books.google.com/?id=1DZz341Pp50C&pg=PA433.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (1704). "Prop VII Theor V". Opticks: Or, A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light. Also Two treatises of the Species and Magnitude of Curvilinear Figures. 1. London. p. 118. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3362k.image.f128.pagination. "All the Colours in the Universe which are made by Light... are either the Colours of homogeneal Lights, or compounded of these..."

- ^ M. J. Lighthill; G. B. Whitham (1955). "On kinematic waves. II. A theory of traffic flow on long crowded roads". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A 229: 281–345. Bibcode 1955RSPSA.229..281L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1955.0088. And: P. I. Richards (1956). "Shockwaves on the highway". Operations Research 4 (1): 42–51. doi:10.1287/opre.4.1.42.

- ^ A. T. Fromhold (1991). "Wave packet solutions". Quantum Mechanics for Applied Physics and Engineering (Reprint of Academic Press 1981 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. pp. 59 ff. ISBN 0486667413. http://books.google.com/?id=3SOwc6npkIwC&pg=PA59. "(p. 61) ...the individual waves move more slowly than the packet and therefore pass back through the packet as it advances"

- ^ Ming Chiang Li (1980). "Electron Interference". In L. Marton & Claire Marton. Advances in Electronics and Electron Physics. 53. Academic Press. p. 271. ISBN 0120146533. http://books.google.com/?id=g5q6tZRwUu4C&pg=PA271.

- ^ See for example Walter Greiner, D. Allan Bromley (2007). Quantum Mechanics (2 ed.). Springer. p. 60. ISBN 3540674586. http://books.google.com/?id=7qCMUfwoQcAC&pg=PA60. and John Joseph Gilman (2003). Electronic basis of the strength of materials. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0521620058. http://books.google.com/?id=YWd7zHU0U7UC&pg=PA57.,Donald D. Fitts (1999). Principles of quantum mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0521658411. http://books.google.com/?id=8t4DiXKIvRgC&pg=PA17..

- ^ Chiang C. Mei (1989). The applied dynamics of ocean surface waves (2nd ed.). World Scientific. p. 47. ISBN 9971507897. http://books.google.com/?id=WHMNEL-9lqkC&pg=PA47.

- ^ Walter Greiner, D. Allan Bromley (2007). Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 60. ISBN 3540674586. http://books.google.com/?id=7qCMUfwoQcAC&pg=PA60.

- ^ Siegmund Brandt, Hans Dieter Dahmen (2001). The picture book of quantum mechanics (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 23. ISBN 0387951415. http://books.google.com/?id=VM4GFlzHg34C&pg=PA23.

- ^ Cyrus D. Cantrell (2000). Modern mathematical methods for physicists and engineers. Cambridge University Press. p. 677. ISBN 0521598273. http://books.google.com/?id=QKsiFdOvcwsC&pg=PA677.

See also

- Audience wave

- Beat waves

- Capillary waves

- Cymatics

- Doppler effect

- Envelope detector

- Group velocity

- Harmonic

- Inertial wave

- List of wave topics

- List of waves named after people

- Ocean surface wave

- Phase velocity

- Reaction-diffusion equation

- Resonance

- Ripple tank

- Rogue wave (oceanography)

- Shallow water equations

- Shive wave machine

- Standing wave

- Transmission medium

- Wave turbulence

- Waves in plasmas

Sources

- Campbell, M. and Greated, C. (1987). The Musician’s Guide to Acoustics. New York: Schirmer Books.

- French, A.P. (1971). Vibrations and Waves (M.I.T. Introductory physics series). Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-393-09936-9. OCLC 163810889.

- Hall, D. E. (1980). Musical Acoustics: An Introduction. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 0534007589..

- Hunt, F. V. (1992). Origins in Acoustics. New York: Acoustical Society of America Press. http://asa.aip.org/publications.html#pub17..

- Ostrovsky, L. A.; Potapov, A. S. (1999). Modulated Waves, Theory and Applications. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801858704..

- Vassilakis, P.N. (2001). Perceptual and Physical Properties of Amplitude Fluctuation and their Musical Significance. Doctoral Dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles.

External links

- Interactive Visual Representation of Waves

- Science Aid: Wave properties—Concise guide aimed at teens

- Simulation of diffraction of water wave passing through a gap

- Simulation of interference of water waves

- Simulation of longitudinal traveling wave

- Simulation of stationary wave on a string

- Simulation of transverse traveling wave

- Sounds Amazing—AS and A-Level learning resource for sound and waves

- chapter from an online textbook

- Simulation of waves on a string

- of longitudinal and transverse mechanical wave

- MIT OpenCourseWare 8.03: Vibrations and Waves Free, independent study course with video lectures, assignments, lecture notes and exams.

| Velocities of waves |

|---|

| Phase velocity • Group velocity • Front velocity • Signal velocity |